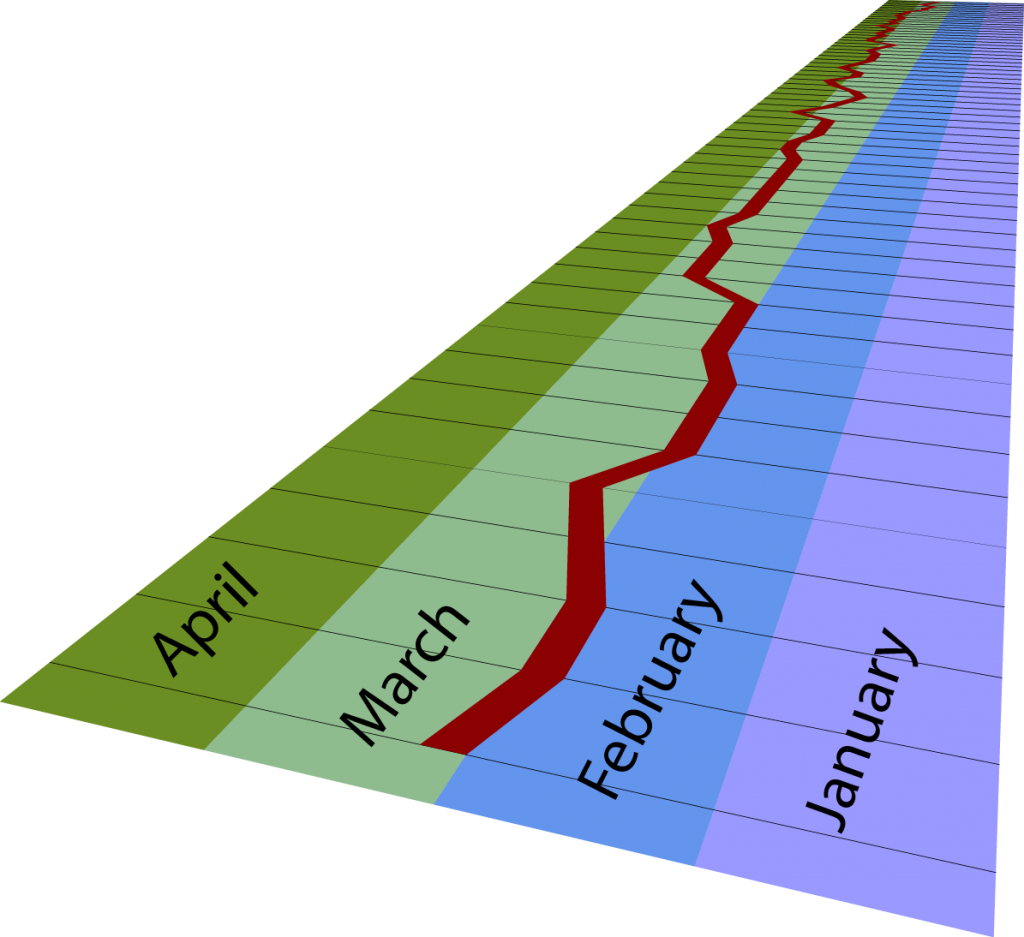

Sundays seem natural for large TV events. Why wouldn’t they? NFL’s Super Bowl has been on Sundays forever. It feels like the proper order of things that the Academy Awards ceremony is also on a Sunday. Every year, somewhere near the end of February, start of March. Yet, a simple dataset of telecast dates points out that this practice is a relatively recent phenomenon and for a long while things were quite different. For a quick summary of the data, look at the chart below: it shows the progression of the ceremony dates from the most distant (1953) to the closest (2014). For more details on why the changes occurred, keep reading on.

It seems like a thing of the deep past, but back when a Borders bookstore was present in every mid-sized town in America, the stores used to carry CDs and DVDs. New releases would become available on Tuesdays, and the store near me would stay open till midnight of Tuesday so that the most avid fans could buy their favorite item a few hours ahead of everybody else. I was curious, why Tuesday? A friend offered an explanation, the only one I’ve heard so far: stores need time to put items on shelves. Studios might have chosen Monday as the release day, but that would mean the stores would have to start shelving on Sundays, which would be difficult due to shortages in staff. Everybody is back from the weekend on Monday and the preparations can proceed in full force. That story stuck with me and when a friend pointed me to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences database and the dates of the awards ceremonies that it contained, very quickly I got the same question: why then and not on a different date?

The chart above plots the number of the week into the year when the ceremony took place. In 1953, the first year of TV broadcasting, it was on the 12th week of the year (March 19, Thursday), in 1966 – on the 17th (April 18th, Monday). For a while, the ceremonies fluctuated around the 13th week and there was a steady annual rhythm: nominations would be announced around February 20th, and the ceremony would be held in late March, early April. In 2004 the Academy has made a radical switch, moving the whole process ahead by a month: nominations are now revealed in January, and the ceremony is held in late February or early March.

There has been some variation in the day of the week chosen for the ceremony:

The ceremonies were predominantly held on Mondays (2nd day of week), never on Saturdays, and, until 1998, only once on a Sunday (March 25, 1985). The ceremony of 1998 was the beginning of the current era, with telecasts set for Sundays.

Using some background research, it appears that, in a nutshell, the history of Oscar telecasts is the history of the uneasy relationship between the Academy and the film industry represented by the powerful studios.

The Academy is a nonprofit: its membership fees are not large enough to cover the costs of the ceremony, and it has to rely on outside funds. The very first telecast, on March 19, 1953, came to be due to the withdrawal of financial support by four of the major eight (at the time) studios (NY Times 1953-01-16). The ceremony was rescued by the deal with NBC-RCA which paid $100,000 for the rights to broadcast the event on TV and radio. A year later NBC also received a six-year deal giving it the rights to cover the nominations ceremony. It is a sign of dominance of television in the 1950s that the U.S. viewership of the 1954 ceremony was estimated at 40 million people: larger than now.

The first telecast, even though it was inevitable, was a remarkable event. Among various paradigms of evolution, there is one called “punctuated equilibrium” – things stay in equilibrium for a long period of time until a juncture – a point in time – when an abrupt change happens. The movie industry was resisting TV broadcasting for a while, but a temporary withdrawal from the coalition by a small number of executives has opened the floodgates, so to speak.

In 1958 the studios agreed to fund the ceremonies again. This alliance has lasted only three years. In the words of film historian Robert Osborne about the 1959 Oscars (the ceremony of April 4, 1960), “… It was the last time the motion picture industry sponsored the Academy ceremony. The financial burden has become too steep, and — due to one-studio sweeps such as Gigi and Ben-Hur — it had become increasingly difficult to get studios to pay for an expensive telecast that might spotlight a rival’s product.”

Left in the vacuum, the Academy has switched the broadcasters and signed a five-year deal with ABC. This was followed by a brief period of partnership with NBC, and since 1976 ABC has held the broadcast rights again.

What about the switch to Sunday? This has occurred also at a juncture point, when the Academy renegotiated a deal with ABC in 1997. It was an 8-year contract, and it stipulated that the ceremonies will be held on Sundays and at an earlier time (6 pm instead of usual 7). The analogy with Super Bowl is obvious. The first broadcast on the new schedule, though, brought lower viewership numbers. “Oscar Broadcast Lost at Least Nine Million Viewers. Lewinsky, not the Oscars, may be the No. 2 star behind the Super Bowl” went the New York Times headline .

The switch to new calendar in 2004, though, was at the Academy’s initiative. Robert Walker, in a NY Times Sunday Magazine article, Saving Oscar (R), listed several plausible reasons for the switch:

- the Academy’s competition with other organizations (e.g., Screen Actors Guild) that announce their awards early in the year,

- the Academy encouraging studio officials to release major pictures earlier in the year, instead of having them released as late as possible (so they would not fade in the minds of the Academy members)

- an expectation among major studios that a shorter advertisement and promotion season would “weed out” the competition posed by smaller studios with less resources, and

- the realization that the Oscars now is a brand, like Coca-Cola or Tide and, “All brands need upkeep, need polishing, refurbishing, retrofitting”, as Walker quoted Terry Press of DreamWorks.

Walker was writing in November 2003. It could be argued that the spread of digital technologies made it easier for the smaller film-makers to survive. The large factors, though, are still at play. Studios invest tens of millions of dollars to promote their films. John Atkinson, in The Oscars. Pocket Essentials reported that Miramax has spent up to $14 million promoting Shakespeare in Love and Life is Beautiful in 1997; it surely paid off as Shakespeare in Love garnered 13 nominations, Life is Beautiful – 7. These numbers are probably true for the recent period as well. The rush of new movie releases in November continues, too.

What will happen next? One insight may come from the U.S. presidential elections. If campaigns are any indicator, we should see more push for the earlier Oscar nominations and an earlier ceremony. On the other hand, the human factor may pose a serious barrier: watching films takes time. Some of the archival stories from the 1980s reported delayed voting for the best foreign film because the members did not have a chance to watch them: they were not showing on the East Coast. With DVDs and digital distribution, such delays should be becoming a thing of the past, but with over three hundreds films reviewed for the Best Film award every year, making an educated vote will still be a time consuming process.

I am grateful for the help of Hyunji Ward (profile) and Profs. Scott Higgins and Andrea McCarty from College of Film and the Moving Images at Wesleyan University in researching this story.